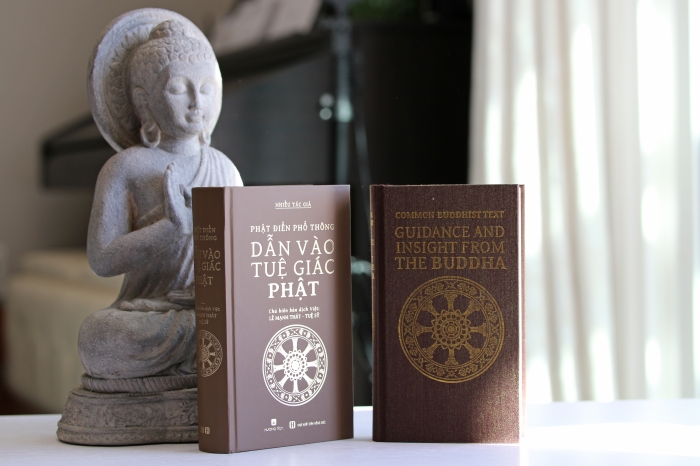

GUIDANCE AND INSIGHT FROM THE BUDDHA

Chief Editor: Venerable Brahmapundit

Editor: Peter Harvey

Translators: Tamás Agócs, Peter Harvey, Dharmacārī Śraddhāpa, P.D. Premasiri, G.A Somaratne,

Venerable Thich Tue Sy

Background to this book,

and its contributors

This book is a project of the International Council of Vesak, based at Mahachulalongkorn-rajavidyalaya University (MCU), Thailand, Vesak being the Buddhist festival celebrating the birth, enlightenment and final nirvana of the Buddha. The project’s aim is to distribute this book for free around the world, especially in hotels, so as to make widely available the rich resources found in the texts of the main Buddhist traditions relating to fundamental issues facing human beings. Through this, its objectives are to increase awareness among Buddhists of their own rich heritage of religious and ethical thinking as well as to increase understanding among non-Buddhists of the fundamental values and principles of Buddhism. It seeks to strike a balance between what is common to the Buddhist traditions and the diversity of perspectives among them.

The book consists of selected translations from Pāli, Sanskrit, Chinese and Tibetan, using a common terminology in English of key Buddhist terms, and maintaining strict scholarly standards. It is to be published first in English and then into the other official UN languages as well as other languages of Buddhist countries.

The Rector of Mahachulalongkorn-rajavidyalaya University, Most Venerable Professor Dr. Brahmapundit, is the guiding Chief Editor of the project, president of its advisory board, and MCU has provided the resources needed for the project.

The proposer and co-ordinator of the project is Cand.philol. Egil Lothe, President of the Buddhist Federation of Norway

The editor and translators

P.H. Peter Harvey: Professor Emeritus of Buddhist Studies, University of Sunderland, U.K., co- founder of the U.K. Association for Buddhist Studies, editor of Buddhist Studies Review, and author of An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics: Foundations, Values and Issues (Cambridge University Press, 2000) and An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices (2nd edn, Cambridge University Press, 2013) – editor of the text, and translator of some passages in The Life of the Historical Buddha and Theravāda sections. Meditation teacher in Samatha Trust tradition.

G.A.S. G.A. Somaratne: Assistant Professor, Centre of Buddhist Studies, University of Hong Kong, formerly Co-director of the Dhammachai Tipitaka Project (DTP) and Rector of the Sri Lanka International Buddhist Academy (SIBA) – main translator of passages in The Life of the Historical Buddha and Theravāda Sangha sections.

P.D.P. P.D. Premasiri: Professor Emeritus of Pāli and Buddhist Studies, Department of Pāli and Buddhist Studies, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, co-founder of the Sri Lanka International Buddhist Academy and President of Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy Sri Lanka – main translator of the passages in the Theravāda Dhamma section.

T.T.S. Most Venerable Thich Tue Sy: Professor Emeritus of Buddhist Studies at Van Hanh University, Vietnam – translator of many of the passages in the Mahāyāna sections.

D.S. Dharmacārī Śraddhāpa: Graduate Researcher, Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, University of Oslo, Norway – co-translator/translator of the passages in the Mahāyāna sections. Member of the Triratna Buddhist Order. He would like to thank Bhikṣuṇī Jianrong, Guttorm Gundersen, and Dr Antonia Ruppel for their invaluable advice and assistance with difficult points in the translation.

Tamás Agócs: Professor in Tibetan Studies, Dharma Gate Buddhist College, Budapest, Hungary – translator of the passages in the Vajrayāna sections.

Compiling Committee

- Chair: Venerable Dr Khammai Dhammasami, Executive Secretary, International Association of Buddhist Universities; Trustee & Fellow, Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, University of Oxford, Professor, ITBMU, Myanmar.

- Cand.philol. Egil Lothe, President of the Buddhist Federation of Norway.

- Prof. Dr. Le Mahn That, Deputy Rector for Academic Affairs, Vietnam Buddhist University , Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

- Ven. Prof. Dr Thich Nhat Tu, Vice Rector, Vietnam Buddhist University, Ho Chi Minh City. Ven. Prof. Dr Jinwol Lee, Dongguk University, Republic of Korea.

- Ven. Prof. Dr Yuanci, Dean of Post-Graduate Studies, Buddhist Academy of China.

- Prof. Dr B. Labh, Head of Dept. of Buddhist Studies, University of Jammu. Co-founder and Secretary of the Indian Society for Buddhist Studies.

- Prof. Dr D. Phillip Stanley, Naropa University, USA, and Head of the Union Catalogue of Buddhist Texts of the International Association of Buddhist Universities.

- Scott Wellenbach, Senior Editor and Translator, Nalanda Translation Committee, Canada. Ven. Associate Prof. Dr Phra Srigambhirayana (Somjin Sammapanno), Deputy Rector for

- Academic Affairs of MCU.

CONTENTS

| INTRODUCTION | 8 |

| General introduction | 8 |

| Introduction on the life of the historical Buddha | 11 |

| Introduction to the Sangha, or community of disciples | 18 |

| Introduction to the selections from Theravāda Buddhism | 19 |

| Introduction to the selections from Mahāyāna Buddhism | 24 |

| Introduction to the selections from Vajrayāna Buddhism | 32 |

| PART I: THE BUDDHA | 37 |

| CHAPTER 1: THE LIFE OF THE HISTORICAL BUDDHA | 37 |

| Conception, birth and early life: passages L.1–6 | 37 |

| The quest for awakening: L.7–9 | 42 |

| Attaining refined, formless states: L.10–11 | 44 |

| The ascetic life of rigorous self-denial: L.12–14 | 46 |

| The awakening and its aftermath: L.15–19 | 50 |

| The achievements and nature of the Buddha: L.20–24 | 54 |

| The Buddha as teacher: L.25–35 | 57 |

| Praise of the Buddha: L.36 | 67 |

| The Buddha’s appearance and manner: L37–39 | 68 |

| Taming and teaching those who resisted or threatened him: L.40–45 | 72 |

| The Buddha’s meditative life and praise for quietness and contentment: L.46–48 | 77 |

| Physical ailments of the Buddha, and compassionate help for the sick: L.49–54 | 79 |

| Sleeping and eating: L.55–57 | 81 |

| Composing and enjoying poetry: L.58–59 | 83 |

| The last months of the Buddha’s life: L.60–69 | 85 |

| CHAPTER 2: DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES ON THE BUDDHA | 94 |

| Theravāda: Th.1–11 | 94 |

| Qualities of the Buddha: Th.1 | 94 |

| The Buddha’s relation to the Dhamma: Th.2–4 | 94 |

| The nature of the Buddha: Th.5 | 95 |

| The Buddha, his perfections built up in past lives as a bodhisatta, and his awakened disciples: Th.6–9 | 95 |

| The status of the Buddha beyond his death: Th.10–11 | 97 |

| Mahāyāna: M.1–13 | 99 |

| Epithets and qualities of the Buddha: M.1–4 | 99 |

| The nature of the Buddha: M.5–8 | 102 |

| A Buddha’s three ‘bodies’: M.9–11 | 104 |

| The Buddha-nature: M.12–13 | 106 |

| Vajrayāna: V.1–6 | 108 |

| The Buddha-nature: V.1 | 108 |

| A Buddha’s three ‘bodies’: V.2 | 109 |

| The five Buddha families: V.3–4 | 110 |

| The Buddha within: V.5–6 | 112 |

| PART II: THE DHAMMA/DHARMA | 116 |

| CHAPTER 3: CHARACTERISTICS OF THE TEACHINGS | 116 |

| Theravāda: Th.12–28 | 116 |

| The qualities of the Dhamma: Th.12–13 | 116 |

| Reasons for choosing to practise Buddhism: Th.14 | 116 |

| Attitudes to other religions: Th.15 | 117 |

| Disputes and tolerance: Th.16–20 | 117 |

| The teachings as having a practical focus: Th.21–24 | 121 |

| The way to liberating knowledge: Th.25–28 | 122 |

| Mahāyāna: M.14–22 | 125 |

| Qualities of the Dharma : M.14–16 | 125 |

| Reasons for choosing to practise Buddhism: M.17 | 127 |

| Disputes and tolerance: M.18–19 | 128 |

| The teachings as means to an end: M.20–21 | 128 |

| The teachings are pitched at different levels, to attract all: M.22 | 129 |

| Vajrayāna: V.7–11 | 130 |

| The qualities of the Dharma: V.7–9 | 130 |

| Concise expositions of the Dharma: V.10–11 | 131 |

| CHAPTER 4: ON SOCIETY AND HUMAN RELATIONSHIPS | 137 |

| Theravāda: Th.29–54 | 137 |

| Good governance: Th.29–31 | 137 |

| Peace, violence and crime: Th.32–36 | 139 |

| Wealth and economic activity: Th.37–43 | 143 |

| Social equality: Th.44–45 | 146 |

| The equality of men and women: Th.46–48 | 148 |

| Good human relationships: Th.49 | 150 |

| Parents and children: Th.50 | 151 |

| Husband and wife: Th.51–53 | 151 |

| Friendship: Th.54 | 153 |

| Mahāyāna: M.23–38 | 153 |

| Good governance: M.23–25 | 153 |

| Peace, violence and crime: M.26–29 | 154 |

| Wealth and economy: M.30–31 | 155 |

| Equality of men and women: M.32–33 | 156 |

| Respect for and gratitude to parents: M.34–35 | 156 |

| Sharing karmic benefit with dead relatives M.36–38 | 158 |

| Vajrayāna: V.12–13 | 160 |

| Advice on compassionate royal policy: V.12 | 160 |

| Reflection on the kindnesses of one’s mother: V.13 | 163 |

| CHAPTER 5: ON HUMAN LIFE | 168 |

| Theravāda: Th.55–78 | 168 |

| The cycle of rebirths (saṃsāra): Th.55–58 | 168 |

| Precious human rebirth: Th.59–61 | 169 |

| Our world in the context of the universe: Th.62–63 | 170 |

| Karma: Th.64–72 | 170 |

| The implications of karma and rebirth for attitudes to others: Th.73–74 | 177 |

| This life and all rebirths entail ageing, sickness and death: Th.75–78 | 177 |

| Mahāyāna: M.39–45 | 180 |

| Our universe: M.39 | 180 |

| Karma: M.40–42 | 181 |

| Precious human birth: M.43 | 184 |

| Impermanence: M.44–45 | 184 |

| Vajrayāna: V.14–23 | 185 |

| Precious human birth: V.14–16 | 185 |

| The pains of saṃsāra: V.17–23 | 188 |

| CHAPTER 6: THE BUDDHIST PATH AND ITS PRACTICE | 194 |

| Theravāda: Th.79–101 | 194 |

| Individual responsibility and personal effort: Th.79–84 | 194 |

| The need for virtuous and wise companions as spiritual friends: Th.85–88 | 195 |

| The role and nature of faith: Th.89–92 | 196 |

| Going for refuge to the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha: Th.93 | 197 |

| Devotional activities: Th.94 | 198 |

| Chants on the qualities of the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha that bring protection and blessing: Th.95–96 | 198 |

| Ethical discipline, meditation, wisdom: Th.97–98 | 200 |

| The noble eightfold path: the middle way of practice Th.99–101 | 201 |

| Mahāyāna: M.46–76 | 203 |

| Faith: M.46-48 | 203 |

| Going for refuge to the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha: M.49–55 | 205 |

| Individual responsibility and personal effort: M.56–57 | 208 |

| The middle way: M.58–63 | 209 |

| The path of the bodhisattva as superior to those of the disciple and solitary-buddha: M.64–67 | 211 |

| The need for a spiritual teacher: M.68–70 | 214 |

| Developing the awakening-mind (bodhi-citta): M.71–76 | 215 |

| Vajrayāna: V.24–40 | 219 |

| Faith: V.24–26 | 219 |

| Going for refuge to the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha V.27–29 | 220 |

| The spiritual teacher: V.30–31 | 221 |

| Practising the middle way: V.32 | 222 |

| The awakening-mind (bodhi-citta): V.33–9 | 223 |

| Graded stages of the path: V.40 | 227 |

| CHAPTER 7: ETHICS | 229 |

| Theravāda: Th.102–120 | 229 |

| Wholesome and unwholesome actions: Th.102–104 | 229 |

| Generosity: Th.105–109 | 230 |

| Precepts of ethical discipline: Th.110–111 | 232 |

| Right livelihood, and extra precepts: Th.112–113 | 233 |

| Loving kindness and patient acceptance: Th.114–116 | 234 |

| Helping oneself and helping others: Th.117–118 | 236 |

| Caring for animals and the environment: Th.119–120 | 237 |

| Mahāyāna: M.77–108 | 237 |

| The power of goodness: M.77 | 237 |

| Generosity: M.78–79 | 238 |

| The precepts of ethical discipline: M.80–87 | 239 |

| Right livelihood, and extra precepts: M.88–89 | 241 |

| Helping oneself and helping others: M.90–94 | 242 |

| Teaching others: M.95 | 243 |

| Care for animals and the environment: M.96 | 243 |

| Loving kindness and compassion: M.97–99 | 244 |

| The bodhisattva perfections: M.100–106 | 245 |

| The bodhisattva vows and precepts: M.107–108 | 250 |

| Vajrayāna: V.41–54 | 254 |

| Wholesome and unwholesome actions: V.41 | 254 |

| The perfection of generosity: V.42–44 | 254 |

| The perfection of ethical discipline: V.45–48 | 256 |

| The perfection of patient acceptance: V.49–53 | 258 |

| The perfection of vigour: V.54 | 260 |

| CHAPTER 8: MEDITATION | 262 |

| Theravāda: Th.121–142 | 262 |

| The purpose of meditation: Th.121–122 | 262 |

| The mind’s negative underlying tendencies but also bright potential: Th.123–124 | 263 |

| The five hindrances and other defilements: Th.125–128 | 263 |

| The importance of attention: Th.129–131 | 265 |

| Calm (samatha) and insight (vipassanā) meditations: Th.132–133 | 267 |

| Recollection of the qualities of the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha, and of the reality of death: Th.134–135 | 268 |

| Meditation on the four limitless qualities: loving kindness, compassion, empathetic joy and equanimity: Th.136–137 | 269 |

| The four foundations of mindfulness (satipaṭṭhāna) as ways to cultivate insight (vipassanā) and calm (samatha): Th.138 | 269 |

| Mindfulness of breathing (ānāpāna-sati): Th.139 | 273 |

| Meditative absorptions, higher knowledges and formless attainments: Th.140–142 | 275 |

| Mahāyāna: M.109–128 | 278 |

| Preparatory meditations: M.109 | 278 |

| Not being attached to meditation: M.110 | 279 |

| The radiant mind: M.111–112 | 279 |

| Meditation on loving kindness and compassion: M.113 | 280 |

| Recollecting the Buddhas: M.114 | 280 |

| Mindfulness: M.115–116 | 282 |

| Calm (śamatha) meditation and the four meditative absorptions: M.117–120 | 283 |

| Insight (vipaśyanā) meditation: M.121–123 | 285 |

| Chan/Zen meditation: M.124–128 | 286 |

| Vajrayāna: V.55–70 | 291 |

| Giving up distractions: V.55–56 | 291 |

| Meditative concentration: V.57 | 293 |

| Meditative antidotes for the various defilements: V.58–64 | 293 |

| Meditation on the four limitless qualities: V.65–68 | 295 |

| The four mindfulnesses: V.69 | 298 |

| Meditation on the nature of mind: V.70 | 299 |

| CHAPTER 9: WISDOM | 301 |

| Theravāda: Th.143–179 | 301 |

| The nature of wisdom: Th.143–148 | 301 |

| Suffering and the four Truths of the Noble Ones: Th.149–155 | 302 |

| Dependent arising and how suffering originates: Th.156–168 | 306 |

| Critical refledctions on the idea of a creator God: Th.169 | 311 |

| The lack of a permanent, essential self: Th.170–179 | 312 |

| Mahāyāna: M.129–150 | 317 |

| The nature of wisdom: M.129 | 317 |

| Dependent arising: M.130–131 | 317 |

| Critical refledctions on the idea of a creator God: M.132 | 319 |

| The lack of a permanent, essential self: M.133–136 | 320 |

| Emptiness of inherent nature/inherent existence: M.137–141 | 323 |

| Mind-only and emptiness of subject-object duality: M.142–143 | 327 |

| The Buddha-nature as a positive reality : M.144–147 | 330 |

| The radical interrelationship of all: M.148-150 | 332 |

| Vajrayāna: V.71–76 | 335 |

| The three types of wisdom: V.71–73 | 335 |

| Dependent arising: V.74 | 336 |

| Insight into the lack of identity: V.75–76 | 338 |

| CHAPTER 10: THE GOALS OF BUDDHISM | 343 |

| Theravāda: 180–188 | 343 |

| Happiness in this and future lives | 343 |

| Definitive spiritual breakthroughs | 343 |

| Nirvana: Th.180–188 | 343 |

| Mahāyāna: M.151–159 | 346 |

| Happiness in this and future lives | 346 |

| Definitive spiritual breakthroughs | 347 |

| Nirvana: M.151–155 | 347 |

| Buddhahood: M.156–158 | 351 |

| Pure Lands: M.159 | 353 |

| Vajrayāna: V.77–83 | 355 |

| Happiness in this and future lives: V.77 | 355 |

| Definitive spiritual breakthroughs: V.78 | 356 |

| Nirvana: V.79 | 356 |

| Activities of the Buddha: V.80-83 | 357 |

| PART III THE SANGHA OR SPIRITUAL ‘COMMUNITY’ | 359 |

| CHAPTER 11: MONASTIC AND LAY DISCIPLES AND NOBLE PERSONS | 359 |

| Theravāda Th.189–211 | 359 |

| The Buddha’s community of monastic and lay disciples: Th.189–190 | 359 |

| The monastic Sangha: Th.191–192 | 359 |

| Monastic discipline: Th.193–198 | 360 |

| Types of noble disciples: Th.199–204 | 363 |

| Arahants: Th.205–211 | 366 |

| Mahāyāna: M.160–164 | 368 |

| Lay and monastic bodhisattvas: M.160–162 | 368 |

| Monastic discipline: M.163–164 | 369 |

| Vajrayāna: V.85 | 371 |

| Monastic life: V.85 | 371 |

| CHAPTER 12: EXEMPLARY LIVES | 374 |

| Theravāda: Th.212–231 | 374 |

| Great arahant monk disciples: Th.212–219 | 374 |

| Great arahant nun disciples: Th.220–225 | 378 |

| Great laymen and laywomen disciples: Th.226–231 | 382 |

| Mahāyāna: M.165–168 | 384 |

| Great monastic disciples: M.165–167 | 384 |

| Great lay disciples: M.168 | 389 |

| Vajrayāna: V.86–91 | 390 |

| Great accomplished ones: V.86–91 | 390 |

| APPENDIXES | 398 |

| Buddhanet’s World Buddhist Directory | 398 |

| To hear some Buddhist chanting | 398 |

| Books on Buddhism | 398 |

| Printed translations and anthologies of translations | 399 |

| Web sources on Buddhism, including translations | 410 |

| Glossary/index of key Buddhist terms and names | 411 |

INTRODUCTION

General introduction

1

This book offers a selection from a broad range of Buddhist texts. You will find here passages that may inspire, guide and challenge you. Overall, they give a picture of this great tradition as it has been lived down the centuries. Welcome!

You may be familiar with some aspects of Buddhism, or it may be quite new to you. It is generally included among the ‘religions’ of the world. This is not inappropriate, for while it is not a ‘religion’ in the sense of being focussed on a ‘God’ seen as the creator of the world, it does accept various kinds of spiritual beings, and emphasizes the potential in human beings for great spiritual transformation. As well as its ‘religious’ aspects, though, Buddhism has strong psychological, philosophical and ethical aspects.

Its aim is to understand the roots of human suffering, and to undermine and dissolve these, building on a bright potential for goodness that it sees as obscured by ingrained bad habits of thought, emotion and action. There is currently a surge of interest in the uses of ‘mindfulness’ – something central to Buddhism – in helping people to deal with such things as stress, recurrent depression, and ongoing physical pain. The UK National Health Service, for example, recommends mindfulness practice as a way to help depressed people from being drawn by negative thoughts back into another episode of depression (see *Th.138 introduction).

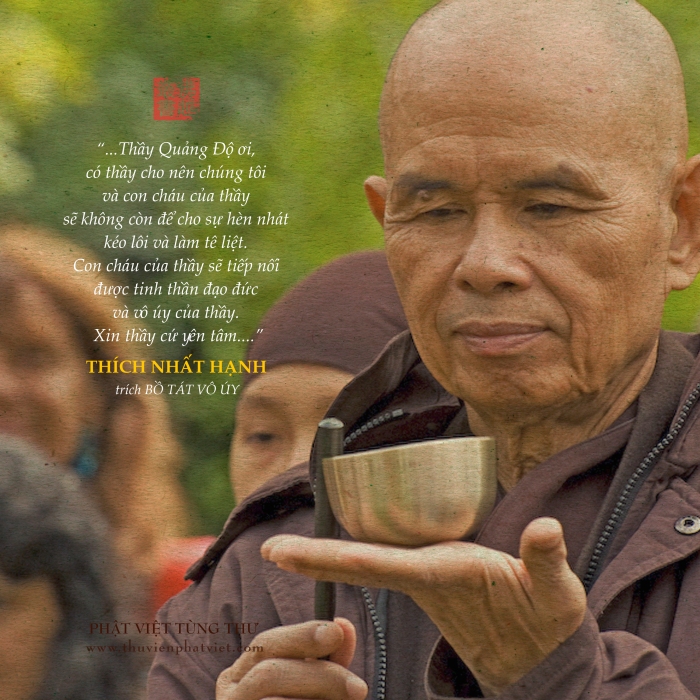

Buddhist teachings talk a lot about suffering, which in the past has made some people see it as pessimistic. But the point of talking about suffering is to help one learn how to overcome it, through methods that help bring calm and joy, and a letting go of accumulated stresses. Any well-made image of the Buddha shows him with a gentle smile of calm repose:

The Buddha taught in a way that did not demand belief, but reflection and contemplation. It has its various teachings and doctrines, but most of all it is a set of practices that helps one:

- to behave in a more considerate and kindly way, for the true benefit and happiness of oneself and others,

- to learn to nurture more positive and helpful attitudes and states of mind, which bring calm, mental composure and inner strength, and to recognize and let go of the causes of stress,

- to develop a wiser understanding of the nature of life, including human limitations and human

2 The age and influence of Buddhism

The history of Buddhism spans around 2,500 years from its origin in India with Siddhattha Gotama,[1] through its spread to most parts of Asia and, in the twentieth and twenty first centuries, to the West. Professor Richard Gombrich of Oxford University holds that the Buddha was ‘one of the most brilliant and original thinkers of all time’,[2] whose ‘ideas should form part of the education of every child, the world over’, which ‘would make the world a more civilized place, both gentler and more intelligent’ (p. 1), and with Buddhism, at least in numerical terms, as ‘the greatest movement in the entire history of human ideas’ (p. 194). While its fortunes have waxed and waned over the ages, over half the present world population live in areas where Buddhism is, or has once been, a dominant cultural tradition.

3 Buddhism as containing different ways of exploring its unifying themes

In an ancient tradition, and one that lacks a central authority, it is not surprising that differences developed over time, which applied the Buddha’s insights in a variety of ways. The different traditions developed in India, and then further evolved as Buddhism spread throughout Asia. In Buddhist history, while the different traditions engaged in critical debate, they were respectful of and influenced each other, so that physical conflict between them has been rare, and when it has occurred it has been mainly due to political factors.

This book contains teachings from the three main overall Buddhist traditions found in Asia. It seeks to particularly illustrate what they have in common but also to show their respective emphases and teachings.

4 The organization of this book

This book is divided into three main parts: i) the life and nature of the Buddha ii) the Dhamma/Dharma, or Buddhist teachings, and iii) the Sangha or spiritual community. Each chapter except the first is divided into three sections, containing selected passages from the texts of the three main Buddhist traditions: Theravāda, Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna.

Each of the passages is labelled with a letter to show what tradition it comes from – respectively Th., M. and V. – and a number, for ease of cross-referencing. Passages in the first chapter, on the life of the Buddha, are labelled with the letter L. You can either browse and dip into the book where you like, or read it from the beginning. For referring back to material in the introductions, section numbers preceded by relevant letters are used: GI. for General introduction, LI. for Introduction on the life of the historical Buddha, SI. for Introduction to the Sangha, and ThI., MI., and VI. respectively for the Introductions to the selections from Theravāda, Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism. So, for example, 3 refers to section 3 of the Mahāyāna introduction.

Note that, in the translations, where material is added within round brackets, this is for clarification of meaning. Where material is added within square brackets, this is to briefly summarise a section of the passage that has been omitted.

5 The Buddha and Buddhas

The English term ‘Buddhism’ correctly indicates that the religion is characterized by a devotion to ‘the Buddha’, ‘Buddhas’ or ‘Buddha-hood’. ‘Buddha’ is not a proper name, but a descriptive title meaning ‘Awakened One’ or ‘Enlightened One’. This implies that most people are seen, in a spiritual sense, as being asleep – unaware of how things really are. The person known as ‘the Buddha’ refers to the Buddha known to history, Gotama. From its earliest times, though, Buddhism has referred to other Buddhas who have lived on earth in distant past ages, or who will do so in the future; the Mahāyāna tradition also talks of many Buddhas currently existing in other parts of the universe. All such Buddhas, known as ‘perfectly awakened Buddhas’ (Pāli sammā-sambuddhas, Sanskrit[3] samyak- sambuddha), are nevertheless seen as occurring only rarely within the vast and ancient cosmos. More common are those who are ‘buddhas’ in a lesser sense, who have awakened to the nature of reality by practising in accordance with the guidance of a perfectly awakened Buddha such as Gotama. Vajrayāna Buddhism also recognizes certain humans as manifestations on earth of Buddhas of other world systems known as Buddha-lands.

As the term ‘Buddha’ does not exclusively refer to a unique individual, Gotama Buddha, Buddhism is less focussed on the person of its founder than is, for example, Christianity. The emphasis in Buddhism is on the teachings of the Buddha(s), and the ‘awakening’ or ‘enlightenment’ that these are seen to lead to. Nevertheless, Buddhists do show great reverence for Gotama as a supreme teacher and an exemplar of the ultimate goal that all Buddhists strive for, so that probably more images of him exist than of any other historical figure.

6 The Dhamma/Dharma

In its long history, Buddhism has used a variety of teachings and means to help people first develop a calmer, more integrated and compassionate personality, and then ‘wake up’ from restricting delusions: delusions which cause grasping and thus suffering for an individual and those they interact with.

The guide for this process of transformation has been the ‘Dhamma’ (in Pāli, Dharma in Sanskrit): meaning the patterns of reality and cosmic law-orderliness discovered by the Buddha(s), Buddhist teachings, the Buddhist path of practice, and the goal of Buddhism: the timeless nirvana (Pāli nibbāna, Sanskrit nirvāṇa). Buddhism thus essentially consists of understanding, practising and realizing Dhamma.

7 The Sangha

The most important bearers of the Buddhist tradition have been the monks and nuns who make up the Buddhist Saṅgha or monastic ‘Community’. From approximately a hundred years after the death of Gotama, certain differences arose in the Sangha, which gradually led to the development of a number of monastic fraternities, each following a slightly different monastic code, and to different schools of thought. In some contexts, the term saṅgha refers to the ‘Noble’ Sangha of those, monastic or lay, who are fully or partially awakened.

8 The three main Buddhist traditions and their relationship

All branches of the monastic Sangha trace their ordination-line back to one or other of the early fraternities; but of the early schools of thought, only that which became known as the Theravāda has continued to this day. Its name indicates that it purports to follow the ‘teaching’ of the ‘Elders’ (Pāli Thera) of the council held soon after the death of the Buddha to preserve his teaching. While it has not remained static, it has kept close to what we know of the early teachings of Buddhism, and preserved their emphasis on attaining liberation by one’s own efforts, using the Dhamma as guide.

Around the beginning of the Christian era, a movement evolved which led to a new style of Buddhism known as the Mahāyāna, or ‘Great Vehicle’. The Mahāyāna puts more overt emphasis on compassion, a quality which is the heart of its ‘bodhisattva path’ leading to complete Buddhahood for the sake of liberating countless sentient beings. The Mahāyāna also includes devotion to a number of figures whose worship can help people to transform themselves – holy saviour beings, more or less. It also offers a range of sophisticated philosophies, which extend the implications of the earlier teachings. In the course of time, in India and beyond, the Mahāyāna produced many schools of its own, such as Zen.

One Mahāyāna group which developed by the sixth century in India, is known as the Mantrayāna, or the ‘Mantra Vehicle’. It is mostly the same as the Mahāyāna in its doctrines, and uses many Mahāyāna texts, but developed a range of powerful new practices to attain the goals of the Mahāyāna, such as the meditative repetitions of sacred words of power (mantra) and visualization practices. It is characterised by the use of texts known as tantras, which concern complex systems of ritual, symbolism and meditation, and its form from the late seventh century is known as the Vajrayāna, or ‘Vajra Vehicle’. Generally translated as ‘diamond’ or ‘thunderbolt’, the vajra is a symbol of the indestructibility and power of the awakened mind. ‘Vajrayāna’ is used in this work as a general term for the tradition which includes it as well as the elements of the Mahāyāna it emphasizes.

While Buddhism is now only a minority religion within the borders of modern India, its spread beyond India means that it is currently found in three areas in Asia:

- Southern Buddhism, where the Theravāda school is found, along with some elements incorporated from the Mahāyāna: Sri Lanka, and four lands of Southeast Asia – Thailand, Burma/Myanmar, Cambodia, It also has a minority presence in the far south of Vietnam, the Yunnan province of China (to the north of Laos), Malaysia, Indonesia, in parts of Bangladesh and India, and more recently in Nepal. In this book, it is referred to as ‘Theravāda’.

- East Asian Buddhism, where the Chinese transmission of Mahāyāna Buddhism is found: China (including Taiwan) except for Tibetan and Mongolian areas, Vietnam, Korea, It also has a minority presence among people of Chinese background in Indonesia and Malaysia. In this book, it is simply referred to as ‘Mahāyāna’.

- Central Asian Buddhism, where the Tibetan transmission of Buddhism, the heir of late Indian Buddhism, is found. Here the Mantrayāna/Vajrayāna version of the Mahāyāna is the dominant form: Tibetan areas within contemporary China and India, and Tibetan and other areas in Nepal; Mongolia, Bhutan, parts of Russia (Buryatia and Kalmykia), and now with a resurgence of it among some in In this book, it is referred to as ‘Vajrayāna’, though it shares many central Mahāyāna ideas with East Asian Buddhism.

These can be seen as like the three main branches of a family. There are ‘family resemblances’ across all three branches, though certain features and forms are more typical of, and sometimes unique to, one of the three branches. Moreover, the ‘family’ is still expanding. Since the nineteenth century, with a large boost in the second half of the twentieth century, Buddhism has, in many of its Asian forms, also been spreading in Europe, the Americas, Australia and New Zealand, as well as being revived in India.

9 The number of Buddhists in the world

The number of Buddhists in the world is approximately as follows: Theravāda Buddhism, 150 million; East Asian Mahāyāna Buddhism, roughly 360 million; Vajrayāna Buddhism 18 million. There are also around 7 million Buddhists outside Asia. This gives an overall total of around 535 million Buddhists. It should be noted though that, in East Asia, aspects of Buddhism are also drawn on by many more who do not identify themselves as exclusively ‘Buddhist’.

Peter Harvey

_______________________________________________

[1] In Pāli, Siddhārtha Gautama in Sanskrit. Pāli and Sanskrit are two related ancient Indian languages, in which Buddhist texts were originally preserved. They belong to the same family of languages as Greek and Latin, and through these have a link to European languages.

[2] What the Buddha Thought, London, Equinox, 2009, p.vii.

[3] Generally abbreviated in this book as Skt.